Secret Bacon

“I have been induced to think, that if there were a beam of knowledge derived from God upon any man in these modern times, it was upon him.”

Dr William Rawley: 'Life of Sir Francis Bacon', prefaced to Resuscitatio – 1657

Open and Secret

Most people have both a public and a private life, as also an outer and an inner life, the one being open and the other being secret. Francis Bacon had these polarities in an exceptional way, partly natural, partly forced upon him, and partly chosen. However, polarities are an essential, inescapable part of life and can be very creative, such as strife and friendship which, as Bacon pointed out, “are the spurs of motions and the keys of works”. 1 We can also infer from the evidence available that he was successful in balancing and using these opposites creatively, and that to some degree—seemingly to a very great degree—he reached that level of illumination known as knowledge of God, or knowledge of Love, which is God; hence he could speak about it from a position of real knowledge, not just speculation, and earnestly promote its practice in all walks of life.

Over the years many speculations of various kinds have been made about Bacon’s private life and inner life. There is evidence, however, to show that he was a mystic and seer as well as a poet, philosopher and scientist by nature, and in this respect perhaps one of the best accounts of Bacon’s private as well as inner life by someone who knew him personally is given by his private chaplain, friend and literary executor, William Rawley:-

I have been induced to think that if there were a beam of knowledge derived from God upon any man in these modern times, it was upon him. For though he was a great reader of books, yet he had not his knowledge from books but from some grounds and notions from within himself. Which, notwithstanding, he vented with great caution and circumspection. … This lord was religious: for though the world be apt to suspect and prejudge great wits and politicks to have somewhat of the atheist, yet he was conversant with God: as appeareth by several passages throughout the whole current of his writings. Otherwise he should have crossed his own principles, which were: that a little philosophy maketh men apt to forget God, as attributing too much to second causes, but depths of philosophy bringeth a man back to God again. Now, I am sure, there is no man that will deny him, or account otherwise of him, but to have been a deep philosopher. And not only so, but he was able to render a reason of the hope which was in him, which that writing of his, of the Confession of the Faith, does abundantly testify. He repaired frequently, when his health would permit him, to the service of the church; to hear sermons; to the administration of the sacrament of the Blessed Body and Blood of Christ; and died in the true faith, established in the Church of England. 2

This is an account or perception of the inner, private man, of whom the outer self or personality was known to the world as Francis Bacon. It also makes sense because one of the most essential parts of Bacon’s teaching is that Philosophy (and hence the philosopher) should be the servant of Divinity and get to know that Divinity—and he always set out to practice what he preached.

The Divinity referred to in this context is Sophia, a Greek name for the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia), whilst 'philo' means love: hence philosophy is the love of Wisdom, and the philosopher is a person who loves Wisdom and is a friend of Wisdom. Bacon, moreover, makes it clear in his writings that this Wisdom is that of Divine Love, the fundamental nature of God, and that to become wise we need to become loving and to act in love. This is what Bacon understood and knew as a truly "deep philosopher"; but such depth tends to be, by its very nature, secret (i.e. not recognised or understood by others).

A good part of Bacon’s outer self was also secret or veiled, except to a select few. Some of the need for this secrecy was forced upon Bacon, whilst in other instances secrecy was deliberately chosen by him. If, as the evidence suggests, he was in reality the natural son of Queen Elizabeth I and potential heir to the throne of England (if the Queen had chosen to proclaim him publicly as such), then the issue of his birth and true parentage was a secret that was certainly forced upon him and in which he had no choice in the matter. Also his intelligence work for the Queen, by the nature of the work, needed to remain secret except to those who needed to know. His more private legal work and advisory role for both Queen Elizabeth and later King James would also fall into this category.

Perhaps one should further add to this category Bacon’s secrecy as a poet—that is, as a “professed poet” writing poetry and plays in a professional and public way; for to become known as a professional poet in those days would have not only been frowned upon as a gentleman, courtier and member of the aristocracy (i.e. as a son of the Lord Keeper, Sir Nicholas Bacon, or, from the Queen’s point of view, as her son, if he was her son), but also precluded him from acting as the Queen’s (and later, King’s) Counsel, or obtaining any further official position at court or in government, which he wanted. (See ‘Shakespeare’.)

Hide and Seek

However, it also suited Bacon to veil himself as the author of poetic works such as the Shakespeare works, as he seriously believed in the biblical teaching that man is made in the image or likeness of God and therefore should do his or her best to imitate God and work as God works. As Bacon defined it, the purpose of mankind is to know the truth, and we can only know the truth by experiencing it, which means practising or living it. Several times in his writings he pointedly refers to the passage in Solomon’s Wisdom (Proverbs 25:2) which states that God has hidden the truth so that man can search for and find it, like a children’s game of hide and seek in which the divine Majesty takes delight. 3 This truth is the Word of God, the Author of all, immanent and hidden in Creation.

Bacon, in hiding his authorship of his poetic works, is imitating the divine Author and setting up a game of hide and seek for the rest of us to play. It is also a game that teaches us Bacon’s method by means of which all truth might be discovered, which he saw as the special gift he was giving humanity and which he said he would teach us by means of a practical example or training lesson. Part of this game involves assisting each other to find the truth, for Bacon pointed out that no person can achieve such a discovery on their own unaided, but that we need each other, if possible organised in teams according to ability and with different roles to play, to do the work cooperatively.

This game of hide and seek, in which we search for the hidden truth, is what in the mystery schools was called a mystery, which was imitated and experienced in the form of sacred drama. Bacon’s involvement in the mystery schools was particularly hinted at by his friend and colleague, Ben Jonson, in an ode that Jonson wrote and spoke specially for Bacon’s 60th birthday in January 1621:-

Hail, happy Genius of this ancient pile!

How comes it all things so about thee smile?

The fire, the wine, the men! and in the midst,

Thou stand’st as if some Mystery thou did’st! 4

The Mystery

Jonson specifically says that Bacon “did” a mystery—not just that he was a mystery but that he was acting a mystery and, moreover, stood in the midst or heart of it. The reference to the fire, the wine and the men suggests something associated with the mysteries of Bacchus-Dionysus, such as Freemasonry which has links with the Dionysiac Artificers (or Architects) of classical times.

Bacchus-Dionysus was celebrated as the founder and patron god of the mysteries—of drama and theatre. Orpheus was a prime exemplar and refounder of the tradition. Both Pythagorus and Plato were initiates of this mystery stream, and some of its fundamental teachings and practices underlie Christianity (e.g. God is Love). It is probably significant that Italian spellings of the name Bacon, used on titlepages of Bacon’s books translated into Italian, was Baco or Bacco, which is an alternative rendering of the Latin name Bacchus.

Spearshaker

The mention of “ancient pile”, which refers to a classical javelin or spear such as that wielded by the “Spearshaker”, Pallas Athena, and also by Apollo, her partner, 5 adds a Rosicrucian and Shakespearean element, linking with both Bacon’s official title, Baron Verulam of Verulam, 6 and also with Bacon’s unofficial title as the group’s Apollo, the Day Star and leader of the Muses, 7 the ‘light’ of Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism.

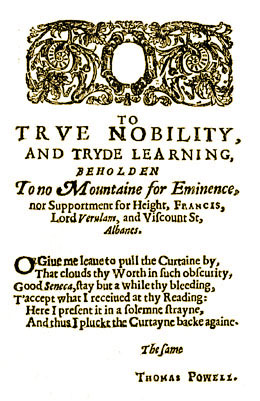

Thomas Powell also uses the mystery theme in his dedicatory poem to Francis Bacon that prefaces his Attourney's Academy (1630), this time very clearly associating it with stage drama because of the likening of Bacon to the classical philosopher-lawyer-writer-playwright Seneca 8 :-

To True Nobility, and tryde learning, beholden

To no Mountaine for Eminence, nor Supportment for Height,

Francis, Lord Verulam, and Viscount St. Albanes.

0 Give me leave to pull the Curtaine by

That clouds thy Worth in such obscurity.

Good Seneca, stay but a while thy bleeding,

T’ accept what I received at thy Reading:

Here I present it in a solemne strayne,

And thus I pluckt the Curtayne backe again.

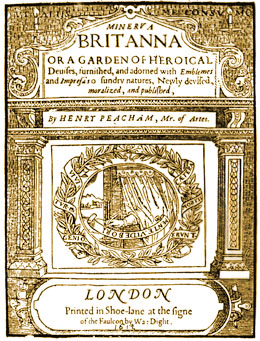

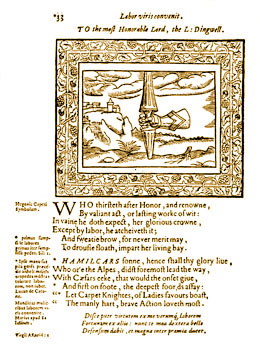

This brings to mind the titlepage illustration of Minerva Britanna by Henry Peacham that was published in 1612. 9 The illustration shows a curtain behind which someone is concealed but whose right arm reaches out in front of it, the hand holding a quill pen which is writing upon a scroll the words “Mente Videbor” (“By the mind I shall be seen”). Two other scrolls on the titlepage state the immortal-mortal (or higher self, lower self) theme that one finds in the Shakespeare sonnets. One is inscribed with “Vivitur in genio”(“One lives in one’s genius”); the other with “Caetera mortis erunt” (“All else passes away”). Both together comprise a quote from the Elegiae in Maecenatem attributed to Virgil.

Moreover, not only does the title “Minerva Britanna” infer Britain’s Pallas Athena, the “Spearshaker” who is the Muse of Shakespeare, but also the emblem on page 33 of Peacham’s book illustrates a stanza from Shakespeare’s poem, Lucrece, which repeats the “Mente Videbor” theme. This stanza is part of the sequence of stanzas that describes a “skilful painting, made for Priam’s Troy”:-

For much imaginary work was there,—

Conceit deceitful, so compact, so kind,

That for Achilles’ image stood his spear

Gripp’d in an armed hand; himself behind

Was left unseen, save to the eye of mind:

A hand, a foot, a face, a leg, a head

Stood for the whole to be imagined. 10

Beneath the emblem picture, the two stanzas of the emblem poem emphasise that all valiant acts and lasting works of wit worthy of honour and renown can only be achieved by sweat and labour. It then offers Hannibal (“Hamilcar’s son”) as an example of manly heart and brave action. The emblem, therefore, by linking it to Achilles and Hannibal, is focused on heroic deeds associated with superhuman warriors or, in Renaissance chivalric terms, with courageous knights, as pointed out in the last two lines of the second stanza.

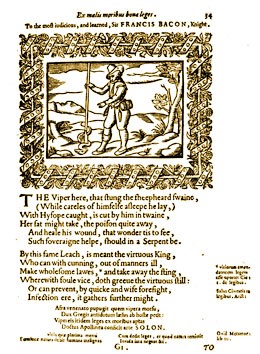

However, the most striking feature of the emblem picture is the gauntleted hand holding the spear, so that the knight (Achilles) is “left unseen, save to the eye of mind”. The hidden knight is described as “himself behind”. This is a clear association with the titlepage picture and “Mente Videbor” motto, except that there is no curtain shown in this emblem picture. However, if one looks at the following emblem 34 (the one “behind” 33), we find a spearshaker revealed who is shaking his spear at a serpent. As this page 34 emblem is dedicated to “the most judicious, and learned, Sir Francis Bacon, Knight”, the spearshaker knight is clearly intended to be Francis Bacon.

In other words, Bacon is the one concealed behind, who is likened in this instance to Achilles, the Greek hero of the Trojan War and greatest warrior of Homer’s Iliad, who was said to be a demigod (i.e. an immortal mortal or mortal immortal). Achilles’ mother was Thetis, the goddess of water, who was identified with Metis, the goddess of wisdom, wise counsel and deep thought.

The spear of Achilles is the subject of the battle between Achilles and Telephus, wherein Achilles gave Telephus a wound that would not heal. Having consulted an oracle, who told Telephus that "he that wounded shall heal", Achilles then healed Telephus, who then became the guide for the voyage to Troy. An alternative version is associated with Odysseus, who reasoned that since the spear had inflicted the wound, therefore the spear should be able to heal it. The association of these two versions of the Achilles-Telephus myth is clearly involved in the symbolism of the Minerva Britanna emblem 34, but with a significant twist. The hint given by choosing Achilles, whose mother was a goddess, as well as the Shakespeare link, should not be missed.

The “Mente Videbor” theme is also to be found in Ben Jonson’s portrait poem prefacing the titlepage of the First Shakespeare Folio: “Reader, look not on his Picture, but his Book”.

In the Shakespeare story, as in Minerva Britanna, the spear is used as a synonym for the pen; hence Ben Jonson’s words in his eulogy to “The AUTHOR Mr. William Shakespeare” in the Shakespeare Folio:-

…Looke how the father’s face

Lives in his issue, even so, the race

Of Shakespeare’s minde, and manners brightly shines

In his well torned, and true filed lines:

In each of which, he seemes to shake a Lance,

As brandish’t at the eyes of Ignorance,

Sweet Swan of Avon!

The symbolism being used is that of Apollo and the Delphic Python. The classical symbolism is equivalent to that of St George and the dragon, wherein the lance signifies a ray of illumination (wisdom), or the means by which wisdom is conveyed, and the dragon (serpent) represents the ignorant mind. The eye is an alternative symbol for the mind.

Cabala

Besides being a master of classical philosophy and mythology, and a high initiate of the mysteries, Bacon was also a master of Cabala (Christian Cabala based on Jewish Kabbalah), which can be seen not only in his understanding of biblical writings but also in the construction of his Great Instauration. The Shakespeare plays, or at least the majority of them, are likewise based on and structured according to Cabalistic knowledge. Such knowledge is related to Hermetic knowledge, the practical aspect of which is known as Alchemy.

Hermes, the legendary founder-teacher of the Hermetic tradition, was an alternative Greek name for the Egyptian god-man Thoth, who in turn was associated with the Atlantean Enoch (‘the Initiate’), known in Hebraic tradition as the first human being to reach the highest heaven in full consciousness and become one with Metatron, the Spirit of the Messiah. Moses, whom the Bible says was learnèd in all the Egyptian wisdom 11 as well as reaching full illumination on Mount Sinai where he was taught directly by Metatron/Enoch, handed on the kabbalistic knowledge that underlies the Torah to the “elect” of Israel.12

That Bacon was a master of Cabala and Hermeticism we can grasp from his Great Instauration and the Shakespeare plays, but there was a time when Bacon considered publishing all of his Great Instauration philosophical works under the pseudonyms of “Valerius Terminus” and “Hermes Stella”, which, if he had carried this out, would have meant that he would have been an almost completely secret man in terms of his philosophy and poetry.

Martyrdom

A further secret or mystery surrounds Bacon’s impeachment in 1621 and death in 1626. Bacon was impeached on charges of corruption and, as a result, to the general public and to this day he is still referred to as a corrupt chancellor. However, when one studies the evidence, it is very clear that the charges were spurious and that he was used as a scapegoat or sacrifice to save the king and his favourite, Buckingham, and possibly the country from a civil uprising.

Strangely, or perhaps pertinently, this impeachment and “fall” of Bacon as Lord Chancellor took place only a few months after he had been created Viscount Saint Alban, a title derived from the name of the saint, not from the town St Albans. This unique title in itself points to the secret of modern Freemasonry’s foundation by its 17th century First Grand Master, (Viscount) Saint Alban. Bacon’s sacrifice, although imposed upon him for other reasons, echoes the sacrifice made by the original Saint Alban, who not only stood up for what he believed in but also protected the priest who had initiated him into Christianity by donning the cloak of the priest and pretending to be him, so as to allow the priest to escape.

Thereafter Bacon was thrown out of active involvement in service to the Crown and country, and spent the next five years in contemplation and studies, together with writing, completing, compiling, editing and publishing as much as he could of his Great Instauration. He saw his fall from grace as divine judgement for devoting too much time to affairs of state rather than focusing more fully on his philosophical mission. Interestingly, from this it appears that what he had planned to do had, in the end, been forced upon him, as William Rawley states in his ‘Life of Bacon’:-

The last five years of his life, being withdrawn from civil affairs and from an active life, he employed wholly in contemplation and studies—a thing whereof his lordship would often speak during his active life, as if he affected to die in the shadow and not in the light; which also may be found in several passages of his works. 13

Bacon, we assume, would not have known that he was destined to die in his 66th year (1626). Not only is this a special number esoterically, being the “octave” of 33, but also it has a direct link with the public birth of “William Shakespeare” as a pseudonym and literary programme, which took place in Bacon’s 33rd year (1593) with the publication of Venus and Adonis, “the first heir” of Shakespeare’s “invention”. One could almost say that things could not have been arranged better.

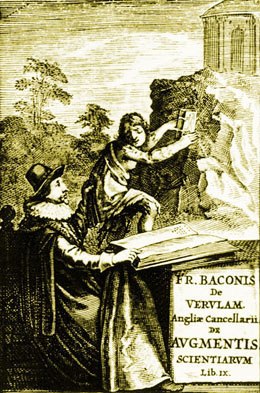

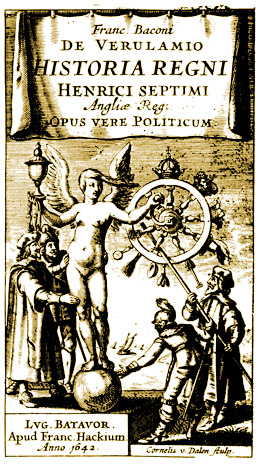

The Third Plato

After his death, Bacon was referred to as “Tertius a Platone, Philosophiæ Princeps” on the frontispiece to the 1640 publication of Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning. This Latin description of Bacon translates as “The Third from Plato, the Leader of Philosophy,” implying that Bacon was perceived as the “Third Plato”. The “First Plato”, who continues to be referred to as Plato, was the 4th century BC Greek poet-philosopher Aristocles, son of Ariston, who took the name Plato as his pseudonym. The “Second Plato” was the 15th century Italian scholar Marsilio Ficino.

Since the name Plato (derived from Greek ap-Leto, meaning “son of Leto”) appears to be a synonym for Apollo, 14 this harmonises with the description of Francis Bacon as an Apollo, as given in the Manes Verulamiani, and of the author Shakespeare as given by Ben Jonson in the Shakespeare First Folio. (See ‘Tributes’).

Plato was the famous pupil of Socrates. It was due to Plato that the thoughts and words of Socrates were recorded and made known. Perhaps not without relevance in terms of Bacon’s story, Socrates was compelled to be a scapegoat or sacrifice for the injustices of the State and was sentenced to death by drinking poison. Shortly before he died, Socrates spoke his last words to Crito: "Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don't forget to pay the debt." This account is given in Plato’s Phaedo, wherein Socrates provides his final proof of the immortality of the soul.

The reported cause of Bacon’s death was that he caught pneumonia as a result of stuffing a chicken with snow in order to see if freezing the bird would preserve its flesh. He then died a few days later, on Easter Day, 9 April 1626.

Besides this analogous link with Plato, Socrates and the Classical mysteries, there is a symbolic link with the Hebraic, Christian and Celtic mysteries.

Secrecy, Cipher and the Art of Discovery

Bacon veiled the secrets about himself, the Rosicrucian and Freemasonic fraternities, the wisdom knowledges, Shakespeare, various treasures, and even some of the key elements of his Great Instauration, by diverse means. These included the use of parables, fables, myths, symbolism, gematria and cryptography (i.e. ciphers, both numerical and geometric).

As he considered mathematics to be a branch of metaphysics and one of the “essential Forms of things, as that it is causative in Nature of a number of effects,” 15 and that “inquiries into nature have the best result when they begin with physics and end in mathematics,” 16 he used it accordingly.

Setting out to imitate the Great Architect of the Universe, who “disposed all things in proportion, number and order”, and who created a game of hide and seek in order that we should gradually discover the hidden truth, Bacon did likewise. The secrets therefore are there to be discovered, with various signposts and aids to discovering the truth provided for us.

All in all, Bacon has designed it in such a way that it trains us in his Art of Discovery, by means of which we might learn how to discover all truth—the truth hidden in Nature, in ourselves, in the Universe.

© Peter Dawkins, FBRT

1. Francis Bacon, History of the Sympathy and Antipathy of Things.

2. William Rawley, ‘The Life of The Right Honourable Francis Bacon, Baron of Verulam, Viscount St. Alban,’ prefaced to Resuscitatio, 1657.

3. “Nay, the same Salomon the king affirmeth directly that the glory of God is to conceal a thing, but the glory of the king is to find it out [Proverbs 25:2], as if according to the innocent play of children the divine Majesty took delight to hide his works, to the end to have them found out; for in naming the king he intendeth man, taking such a condition of man as hath most excellency and greatest commandment of wits and means, alluding also to his own person, being truly one of those clearest burning lamps, whereof himself speaketh in another place, when he saith the spirit of man is as the lamp of god, wherewith he searcheth all inwardness [Proverbs 20:27]…” (Francis Bacon, Valerius Terminus, Of the Interpretation of Nature.)

4. Ben Jonson, ‘Ode for Lord Bacon’s Birthday’ (1621), publ. in Underwood, No.51.

5. “Ancient pile” specifically refers to a javelin or spear (Latin, pīlum, javelin, spear); other meanings of the word ‘pile’ developed much later.

6. ‘Verulam’ roughly means ‘Spear-shaker’ (from Latin veru, javelin; lam, thrash) whilst at the same time being an acceptable abbreviation of Verulamium, the Roman town that previously existed on the site that became part of Gorhambury estate and the town of St Albans.

7. See Tributes to Francis Bacon.

8. Seneca was a philosopher, writer and eminent lawyer as well as a renowned playwright, who wrote many essays on practical ethics, a popular work on astronomy and a number of tragedies in imitation of the Greeks.

9. Henry Peacham, Minerua Britanna or A garden of heroical deuises (London, 1612).

10. Shakespeare, Lucrece, lines 1422-8.

11. Acts 7:22.

12. The convention of using Cabala (with a C) to signify Christian Cabala as distinct from purely Jewish Kabbalah (with a K) is being used on this website.

13. William Rawley, ‘The Life of the Right Honorable Francis Bacon Baron of Verulam, Viscount St. Alban’, included in Resuscitatio, or, Bringing into Publick Light Several Pieces of the Works, Civil, Historical, Philosophical, & Theological, Hitherto Sleeping; of the Right Honourable Francis Bacon....Together with his Lordship's Life (1657).

14. Leto was the mother of the twins, Apollo and Artemis. Their father was Zeus.

15. Francis Bacon: Advancement of Learning, II (1605).

16. Francis Bacon: Novum Organum, VII (1620).

- Rosicrucian Matters & Mathematics

- Baconian-Rosicrucian Ciphers

- The Fra Rosie Cross Cipher 287

- What's in a Name?

- The Mystery of Francis Bacon's Name

- The Good Name

- Tributes to Sir Francis Bacon

- The Two St Albans

- Elias the Artist

- The Secret Signature

- Canonbury Place & Tower

- Advancement of Learning Secrets