The Good Name

“Solomon says, A Good Name is a precious Ointment...”

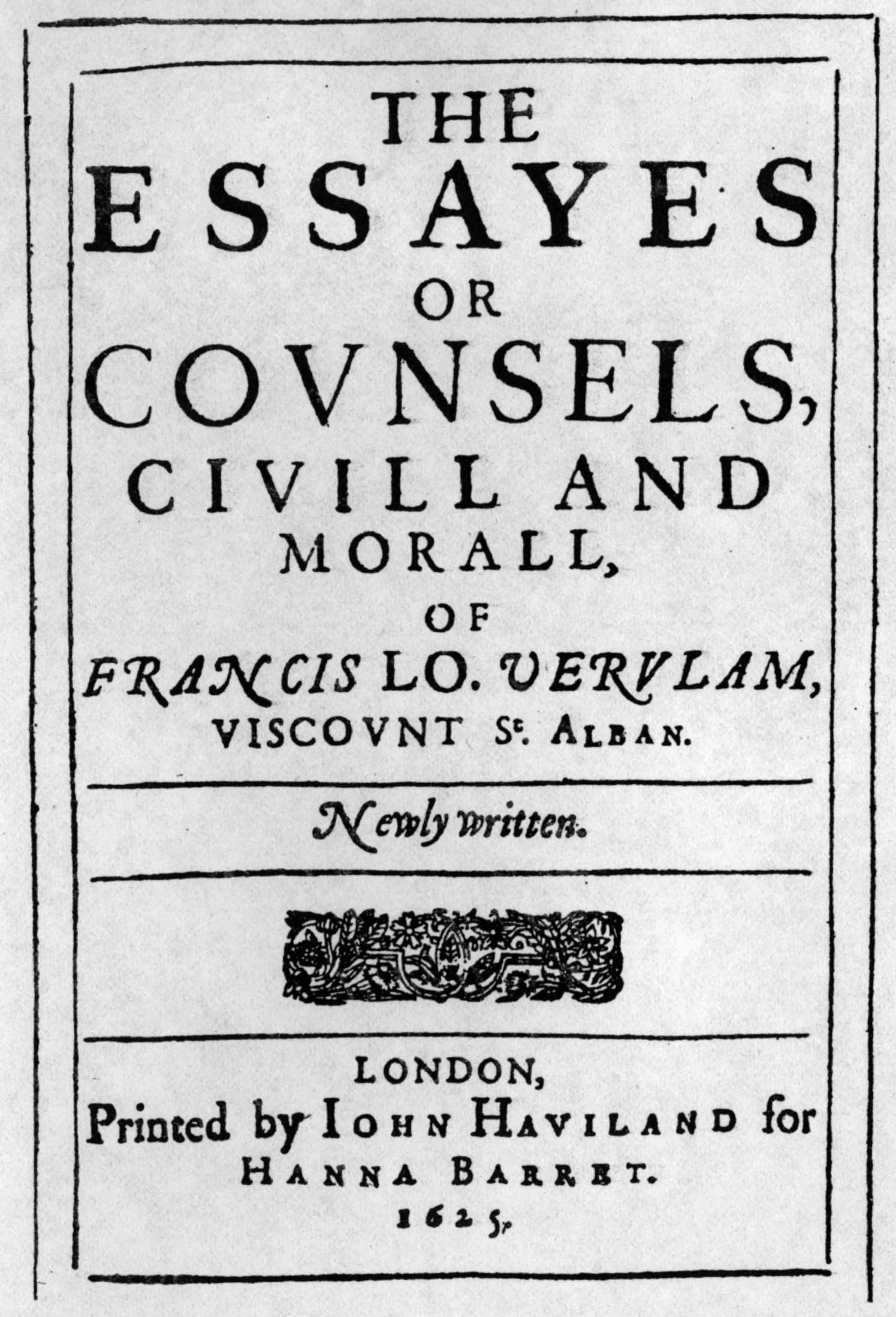

Francis Bacon, Essays: Dedication to the Duke of Buckingham – 1625

Francis Bacon's Good Name

Francis Bacon considered his good name to be the most important and precious part of himself. What does he mean by this?

In His Apologie, In Certaine Imputations Concerning the Late Earle of Essex, he writes:

“I love a good name, but yet as an handmaid and attendant of honesty and virtue.”

He further says, in his essay, Of Riches,

“The gains of ordinary trades and vocations are honest; and furthered by two things chiefly: by diligence, and by a good name, for good and fair dealing.”

And in his will dated 9 April 1626, he writes:

“My name and memory I leave to man's charitable speeches, and to foreign nations, and to the next ages.”

In his essay, Of Goodness & Goodness of Nature, he associates goodness – and hence a good name – with charity, philanthropy and virtue:

“I take goodness in this sense, the affecting of the weal of men, which is that the Grecians call philanthropia; and the word humanity (as it is used) is a little too light to express it. Goodness I call the habit, and goodness of nature, the inclination. This of all virtues, and dignities of the mind, is the greatest; being the character of the Deity: and without it, man is a busy, mischievous, wretched thing; no better than a kind of vermin. Goodness answers to the theological virtue, charity, and admits no excess, but error. The desire of power in excess, caused the angels to fall; the desire of knowledge in excess, caused man to fall: but in charity there is no excess; neither can angel, nor man, come in danger by it....

“But above all if he have St. Paul's perfection, that he would wish to be anathema from Christ, for the salvation of his brethren, it shows much of a divine nature, and a kind of conformity with Christ himself.”

In Bacon's time, and in this quote, mind means ‘soul’, and anathema means ‘consecrated to divine use’. In other words, Bacon considered that the epitome of a good name was that of someone whose life was consecrated to divine use, as was St Paul's, and who accomplished works of charity or philanthropy, according to his or her divine calling, as a service to God and humanity.

And this Francis Bacon certainly did, for his life was dedicated to serving God and humanity by creating the Great Instauration, and by offering himself as an oblation or sacrifice to save the king and his favourite Buckingham, and others, from the fury of Parliament and the people, and thus in the hope of preventing a civil war and all the horrors that accompany such violent revolutions.

As Francis Bacon said in his Preface to the Great Instauration:

“For my own part at least, in obedience to the everlasting love of truth, I have committed myself to the uncertainties and difficulties and solitudes of the ways, and relying on the divine assistance have upheld my mind both against the shocks and embattled ranks of opinion, and against my own private and inward hesitations and scruples, and against the fogs and clouds of nature, and the phantoms flitting about on every side; in the hope of providing at last for the present and future generations guidance more faithful and secure.

“Wherefore, seeing that these things do not depend upon myself, at the outset of the work I most humbly and fervently pray to God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, that remembering the sorrows of mankind and the pilgrimage of this our life wherein we wear out days few and evil, they will vouchsafe through my hands to endow the human family with new mercies.

“This likewise I humbly pray, that things human may not interfere with things divine, and that from the opening of the ways of sense and the increase of natural light there may arise in our minds no incredulity or darkness with regard to the divine mysteries, but rather that the understanding being thereby purified and purged of fancies and vanity, and yet not the less subject and entirely submissive to the divine oracles, may give to faith that which is faith's.

“Lastly, that knowledge being now discharged of that venom which the serpent infused into it, and which makes the mind of man to swell, we may not be wise above measure and sobriety, but cultivate truth in charity.”

Francis Bacon was created Viscount St Alban for good reason – partly because he was the founder of Speculative Freemasonry in England, just as the original St Alban had founded Operative Freemasonry in Roman Britain, and partly because he had lived a saint-like life, devoted to helping people – and, like the original St Alban, sacrificed himself in order to save others.

As Thomas Vincent of Trinity College, Cambridge, said in his tribute to Francis Bacon, Lord St Alban, published in the Manes Verulamiani (1616) shortly after Bacon’s death:

“Those Fates, O Francis, can but take thy clay; Thy better part – mind, reason, and good name – survive the body gladly rendered up.”

Sir Tobie Matthew, in his Dedicatory Letter prefacing an Italian version of Bacon’s Essays, titled Saggi Morali del Signore Francesco Bacono (1617), writes:

“Praise is not confined to the qualities of his intellect, but applies as well to those which are matters of the heart, the will and moral virtue; being a man both sweet in his ways and conversation, grave in his judgments, invariable in his fortunes, splendid in his expenses, a friend unalterable to his friends, an enemy to no man, a most indefatigable servant to the King, and a most earnest lover of the Public, having all the thoughts of that large heart of his set upon adorning the age in which he lives, and benefiting, as far as possible, the whole human race.

“And I can truly say (having had the honour to know him for many years as well when he was in his lesser fortunes as now he stands at the top and in the full flower of his greatness) that I never yet saw any trace in him of a vindictive mind, whatever injury was done to him, nor ever heard him utter a word to any man’s disadvantage which seemed to proceed from personal feeling against the man, but only (and that too very seldom) from judgment made of him in cold blood.

“It is not his greatness that I admire, but his virtue; it is not the favours I have received from him (infinite though they be) that have thus enthralled and enchained my heart, but his whole life and character; which are such that, if he were of an inferior condition I could not honour him the less, and if he were my enemy, I should not the less love and endeavour to serve him.”

John Aubrey, in his Brief Lives, sums up what was thought about Francis Bacon:

“In short, all that were great and good loved and honoured him.”

Dr William Rawley, Francis Bacon’s chaplain, in his Life of Sir Francis Bacon, summarises the vitally important religious nature of Francis Bacon, Lord St Alban, and his ability to converse with the Divine Wisdom and Love as a true philosopher:

“He was deeply religious, for he was conversant with God and able to render a reason for the hope that was in him.”

In religious terms, the sublimest good name is the Divine Name, for the character or nature of God is goodness. The Name of God is the intelligent form of the Word of God. The Word of God is the Will of God, which is the Divine Wisdom as a creative energy, a force. The Divine Intelligence gives this Word a form, which is the Name.

This Divine Name, which is the Word ensouled in a form, exists macrocosmically, universally; but it also exists microcosmically, such as in the hearts of all living individual beings. The aim of life is to awaken this good name, this divine name, in our hearts, and to enable it to expand into our minds or souls, so that heart and mind are truly united, at-one in a mystical marriage of love.

This good name, the divine name, is the summary or universal law, which Francis Bacon describes as love in action – “the work that God works from the beginning to the end.”[1]

Francis Bacon’s Christian name, with which he was baptised, was ‘Francis’. This was his personal name and, as a Christian name, was his spiritual name – the name that described his ‘good name’ or ‘god-name’ – the name of his particular angel whose purpose he was to help fulfil, and who in turn would help him. ‘Francis’ means ‘free’, and the word ‘free’ is derived from the Sanskrit word fri or pri, meaning ‘love’.

Francis’ surname or family name was ‘Bacon’, which was a link with the Dionysian Mysteries as practised at Eleusis and Athens in Greece, and with the Bardic-Druidic Mysteries of Britain, wherein King Arthur was known as the boar, and his queen as the sow. The boar, when sacrificed as an oblation to God and to help humanity, and well hung and smoked over the fire, became bacon – something that is referred to by Mistress Quickly in Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor, when she says “Hang-hog is latten for Bacon, I warrant you.”[2]

Loss of “Good Name” – Impeachment as Lord Chancellor

Francis Bacon’s “good name” has been badly traduced ever since he was impeached by the House of Lords on 1 May 1621 for supposedly taking bribes, and the Great Seal was taken from him.

The Great Seal was taken from Francis Bacon by the equivalent four lords mentioned in the Shakespeare play, Henry VIII, as taking the Seal from Cardinal Wolsey, whereas it is historically well recorded that only two lords removed the Great Seal from Wolsey.

However, Francis Bacon was not guilty of taking bribes, and he was not corrupt, despite what a great many people have been saying about him for 400 years. He was, as he himself said, “as innocent as any babe born upon St. Innocent’s Day” in terms of the charge of being bribed to pervert the course of justice.

Having taken an oath to obey and serve the king, and having suggested to the King that he was prepared to submit without any defence, as an “oblation” or sacrificial offering, and clearly having been asked by the King to do this, on 24th April 2021 the charges were finally sent to Bacon. By this time Bacon was sick in bed, and he was being given just five days to reply to the charges. There were 28 charges, and each was supplied without any accompanying evidence, which normally would have been required in a Court of Law. However, the House of Lords was not a Court of Law, but purely political.

On 30 April 1621 Francis Bacon, Lord St Alban, sent to the House of Lords a “Confession and humble Submission” in which he began by declaring himself guilty of corruption, but then went on to give his answers to each of the 28 charges. He noted that, with the exception of four doubtful cases (“where the Judge conceives the cause to be at an end by the information of the party, or otherwise, and useth not such diligence as he ought to inquire of it”), not a single fee given to him was a bribe. As for the four doubtful cases, which involved a complexity of multiple court cases for each client, it was later proven by eminent lawyers that Bacon was not guilty of any bribery or corruption.

So, despite it having been proven from the very beginning, and over and over again in succeeding years and centuries, that Bacon was not corrupt, nevertheless a great majority of people have chosen and still continue to call him a corrupt chancellor. One wonders why?

A similar thing applies to Francis Bacon being called a materialist, and his philosophy and science being referred to as being materialistic. Nothing could be further from the truth. Again, Bacon’s “good name” has been traduced. Why?

One answer is that in each case, Bacon has been used as a scapegoat for other people’s faults – for over 400 years!

Loss of “Good Name” – Bacon’s Great Instauration

Concerning his ‘Great Instauration’ of Philosophy and Science – “building a Temple in the human mind,” as he described it – Francis Bacon wrote that Divinity should always be an essential part of any philosophical enquiry, and that Philosophy is the handmaiden of Divinity, the Mistress, and should love and serve her Mistress faithfully.

In other words, a true philosopher loves Sophia, just as the very name ‘philosopher’ means (Greek, philo-sophia, ‘love of Sophia’). If there is no love, and no willingness to serve Sophia, who is all-loving, then one is not a genuine philosopher. Sophia, the Mistress, is the feminine aspect of Divine Wisdom. The male aspect is the Logos (Word). The two are inseparable. Sophia is the Divine Intelligence that gives form to the Word, which form is the Divine Name. Logos and Sophia are the immortal twins of Divine Wisdom, who create the laws of the universe and inspire wisdom into human hearts.

Of all the laws, Bacon considered the supreme summary (universal) law to be love – love in action – just as Jesus Christ and the Orphic-Dionysian Mysteries taught, as also original Hebraism and the Essenes.

Francis Bacon’s ‘Great Instauration’ is about researching not just the physical laws but also the metaphysical laws of nature; and, moreover, the laws underlying the three types of nature – natural nature, human nature, and divine nature. That is to say, we should be researching not only the physical laws but also the metaphysical laws of all three types of nature. This is nature as defined in the dictionary: the fundamental character, disposition, temperament or basic constitution of a living being or thing.

Bacon also wrote that there were two levels of physical laws, material and efficient, and likewise two levels of metaphysical laws, formal and final.

In terms of the two levels of physical laws, it would seem that Bacon was aware of the more etheric counterpart to what we call physical, but which Bacon would call material. In terms of the two levels of metaphysical laws, formal and final, Bacon uses Plato’s word, ‘forms’, which refer to the divine ideas or intelligences, otherwise known as angels, with ‘final’ referring to the ‘final forms’, otherwise known as the great archangels.

Bacon describes the Philosophy of the Great Instauration as being like a Pyramid, founded upon History (observation of facts drawn from experience) and built via Poetry (the “ladder of the intellect”, which is the result of imagination).

Even chemical experiments in the laboratory are the result of imaginative, hence poetic, ideas. As for enquiry into human laws, the Shakespeare plays are examples of such poetic experimentation, with Speculative Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism taking such enquiry and experimentation even further.

The Great Instauration that Francis Bacon inaugurated is clearly intended to bring about a marriage of Divinity and Philosophy – a marriage of heaven and earth, of immortality and mortality, as per the Gemini myth.

© Peter Dawkins, FBRT

[1] Francis Bacon, Wisdom of the Ancients, ‘Cupid or the Atom.’ Bacon's quote is from Ecclesiastes 3:11.

[2] Shakespeare, Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 4, Scene 1, lines 48-49. Wording as given in the original 1623 Shakespeare First Folio. The word “latten” is a pun on ‘Latin’ (into which it is invariably altered by modern editors), but in fact means a mixture of something, in particular a mixed metal identical with or resembling brass. The intended meaning of the statement by Mistress Quickly is, therefore, quite clear and correct, for “hang-hog” is indeed a kind of base mixture of words for bacon; but because bacon is spelt with a capital B, as “Bacon”, Mistress Quickly’s parable is in fact referring to the name Bacon and the story of Sir Nicholas Bacon recounted by Francis Bacon as a parable in his 36th Apothegm. Moreover, as a secret language, it is also referring to the Dionysian Mysteries, which is made clear by the subtle choice of words as well as word-play in the scene. (See Rosicrucian Matters & Mathematics.)